In August 2016 the FASB issued ASU 2016-15, Statement of Cash Flows (Topic 230): Classification of Certain Cash Receipts and Cash Payments (a consensus of the Emerging Issues Task Force), which goes into effect for public business entities whose fiscal years begin after December 15, 2017. The goal of ASU 2016-15 is to reduce diversity in practice in how certain cash receipts and cash payments are presented and classified in the statement of cash flows under Topic 230, Statement of Cash Flows, and other Topics.

With this goal in mind, this ASU addresses eight specific statement of cash flows (SCF) classification issues. They include:

- Debt Prepayment or Debt Extinguishment Costs – Cash payments for debt prepayment or debt extinguishment costs should be classified as cash outflows for financing activities.

- Settlement of Zero-Coupon Debt Instruments or Other Debt Instruments with Coupon Interest Rates That Are Insignificant in Relation to the Effective Interest Rate of the Borrowing – At the settlement of zero-coupon debt instruments or other debt instruments with coupon interest rates that are insignificant in relation to the effective interest rate of the borrowing, the issuer should classify the portion of the cash payment attributable to the accreted interest related to the debt discount as cash outflows for operating activities, and the portion of the cash payment attributable to the principal as cash outflows for financing activities.

- Contingent Consideration Payments Made after a Business Combination – Cash payments not made soon after the acquisition date of a business combination by an acquirer to settle a contingent consideration liability should be separated and classified as cash outflows for financing activities and operating activities. Cash payments up to the amount of the contingent consideration liability recognized at the acquisition date (including measurement-period adjustments) should be classified as financing activities; any excess should be classified as operating activities. Cash payments made soon after the acquisition date of a business combination by an acquirer to settle a contingent consideration liability should be classified as cash outflows for investing activities.

- Proceeds from the Settlement of Insurance Claims – Cash proceeds received from the settlement of insurance claims should be classified on the basis of the related insurance coverage (that is, the nature of the loss). For insurance proceeds that are received in a lumpsum settlement, an entity should determine the classification on the basis of the nature of each loss included in the settlement.

- Proceeds from the Settlement of Corporate-Owned Life Insurance Policies, including Bank-Owned Life Insurance Policies – Cash proceeds received from the settlement of corporate-owned life insurance policies should be classified as cash inflows from investing activities. The cash payments for premiums on corporate-owned policies may be classified as cash outflows for investing activities, operating activities, or a combination of investing and operating activities.

- Distributions Received from Equity Method Investees – When a reporting entity applies the equity method, it should make an accounting policy election to classify distributions received from equity method investees using one of two approaches: (1) cumulative earnings approach or (2) nature of the distribution approach. These two approaches are further described within this ASU. Disclosures related to changes in accounting principle may be required depending on an entity’s elections.

- Beneficial Interests in Securitization Transactions – A transferor’s beneficial interest obtained in a securitization of financial assets should be disclosed as a non-cash activity, and cash receipts from payments on a transferor’s beneficial interests in securitized trade receivables should be classified as cash inflows from investing activities.

- Separately Identifiable Cash Flows and Application of the Predominance Principle – The classification of cash receipts and payments that have aspects of more than one class of cash flows should be determined first by applying specific guidance in GAAP. In the absence of specific guidance, an entity should determine each separately identifiable source or use within the cash receipts and cash payments on the basis of the nature of the underlying cash flows. An entity should then classify each separately identifiable source or use within the cash receipts and payments on the basis of their nature in financing, investing, or operating activities. In situations in which cash receipts and payments have aspects of more than one class of cash flows and cannot be separated by source or use, the appropriate classification should depend on the activity that is likely to be the predominant source or use of cash flows for the item.

Current GAAP is either unclear or does not include specific guidance on these eight SCF classification issues included in the amendments in this ASU. With this in mind, the ASU is an improvement to GAAP because it provides guidance for each of these eight issues, thereby reducing the current and potential future diversity in practice.

Errors in the statement of cash flows

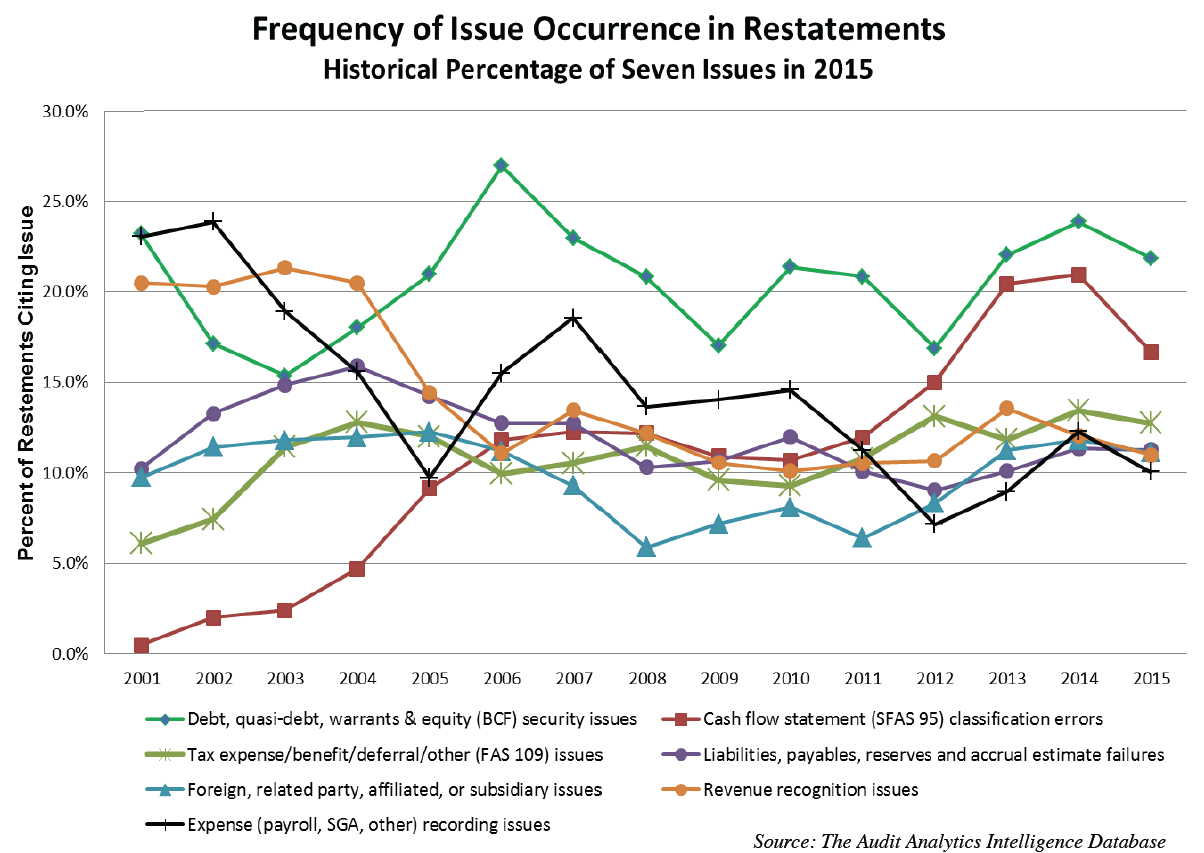

An interesting data point in the context of the SCF is that in the last five years the second most common issue cited in financial statement restatements related to errors in the SCF. The following chart depicts SCF errors compared to six other common restatement issues between 2001 and 2015:

As one can gather, these eight SCF classification issues may be perceived as addressing non-routine transactions. According to the Audit Analytics August 2016 report on SOX 404 Disclosures, which I wrote about in a previous post, in 2015 approximately 5% of auditor attestations cited ineffective internal controls over financial reporting (ICFR) due, at least in part, to SCF classification issues. Although this is a relatively small percentage compared to the total number of ICFR failures in 2015, these SCF classification issues typically related to non-routine transactions.

With the new guidance in ASU 2016-15, we can expect improvements in the disclosures related to the SCF; however, it’s unclear at this juncture what extent of influence the adoption of the ASU will have on mitigating ICFR failures going forward.