Many companies became subject to the provisions of Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) beginning for fiscal years ending on or after November 15, 2004. Specifically, Section 404(a) requires public companies’ annual reports to include the company’s own assessment of internal control over financial reporting (ICFR). Section 404(b) requires an independent auditor’s report on the effectiveness of the company’s ICFR.

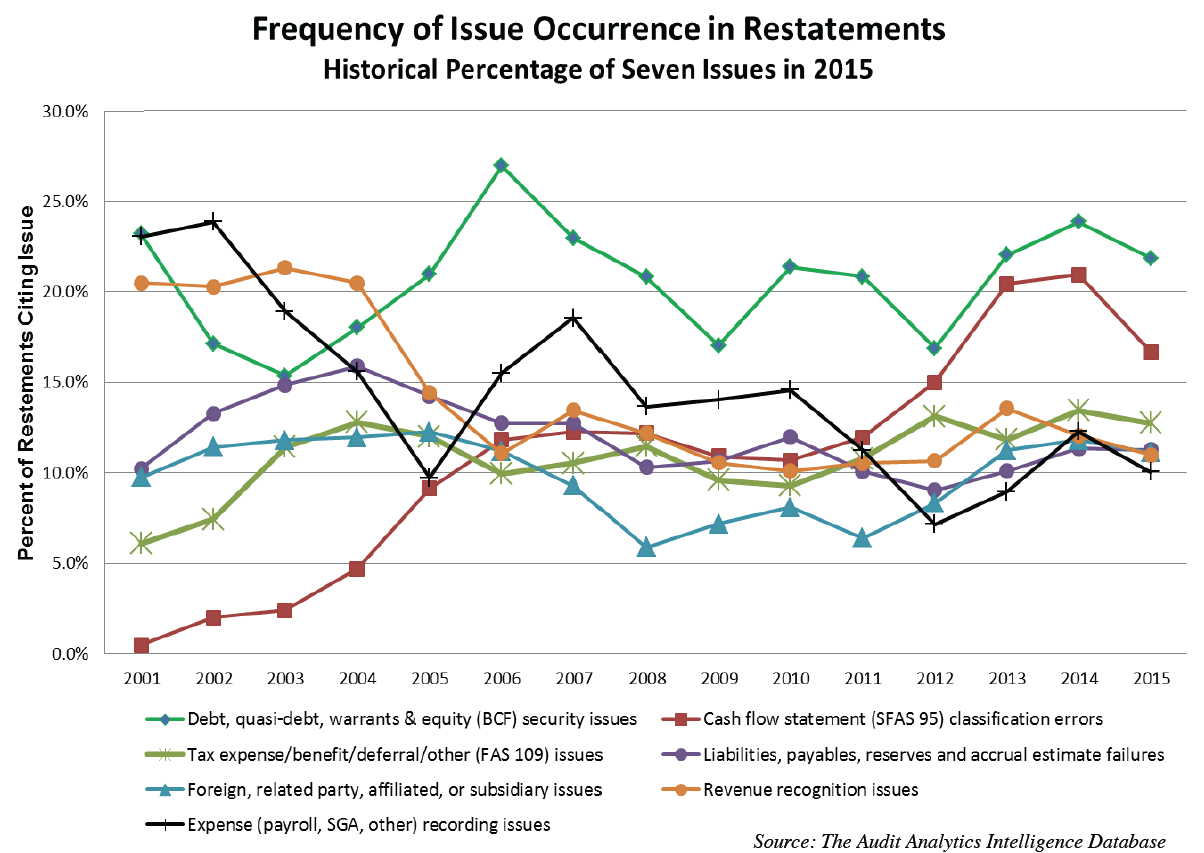

Since the implementation of SOX 12 years ago, we have seen some interesting trends in financial restatement statistics and SEC enforcement trends, which I have written about recently (here and here). In fact, a recent Audit Analytics report has highlighted some key take-aways related to Section 404 disclosures.

Effectiveness of ICFR requiring auditor attestation

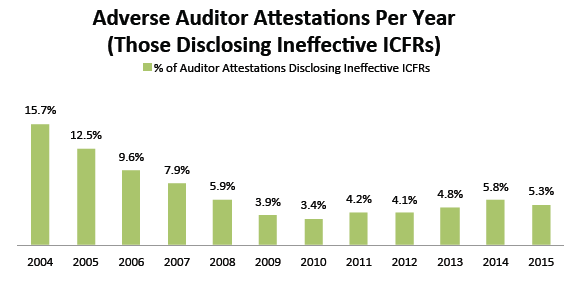

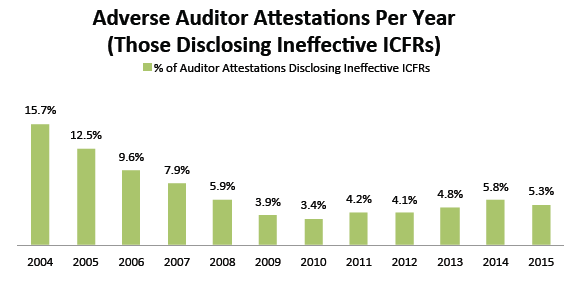

SOX Section 404(b) states that accelerated filers (including large accelerated filers) must provide an independent auditor’s report on the effectiveness of the filer’s ICFR. The following chart shows adverse auditor reports as a percentage of total auditor reports on ICFR on an annual basis within the last 12 years.

For clarification, according to PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 5 (AS 5), An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That Is Integrated with An Audit of Financial Statements, an adverse opinion signifies that at least one material weakness exists within a company’s ICFR.

Naturally, one would expect the first year of implementation, 2004, to yield the least favorable results. To also note is that because the SOX Section 404 requirements went into effect in late 2004, only a portion of companies whose fiscal years ended in 2004 were required to implement these requirements (i.e., those whose fiscal years ended on or after November 15, 2004). This means that a smaller number of companies filed auditor attestations related to fiscal 2004 when compared to fiscal 2005.

What I find interesting about the above chart, and the Audit Analytics report discusses, is the historical “low” in the rate in 2010. In 2010, the PCAOB inspection program began determining if audit firms had obtained adequate evidence to substantiate the auditor’s attestation of management’s assessment regarding the effectiveness of ICFR. The impetus for this was the implementation of AS 5, which became effective in late 2007.

After initially reviewing audit firms’ implementation of AS 5 in 2008 and 2009, the PCAOB’s inspections began in 2010 to focus on inspecting for and reporting on whether firms obtained sufficient evidence to support their audit opinions on the effectiveness of ICFR. Although somewhat unclear, we might gather from the above chart that the PCAOB’s scrutiny of audit firm compliance with AS 5 in 2010 may have re-focused the emphasis of audit firms on improving audit quality in 2011 (when compared to 2010).

Key areas of adverse auditor reports

Among those auditor reports with an adverse audit opinion on ICFR, the Audit Analytics report identifies the following internal controls issues with the highest frequency in 2015:

|

Ineffective ICFR issues

|

Total number of attestations

|

As % of total attestations citing ineffective ICFR

|

| Material and/or numerous auditor and/or management adjustments |

118

|

58%

|

| Inadequate accounting personnel resources, competency, and/or training |

105

|

52%

|

| IT, software, security, and access controls |

60

|

30%

|

| Segregation of duties and/or design of controls |

50

|

25%

|

| Controls related to non-routine transactions |

39

|

19%

|

As illustrated in the table above, the top reason for ineffective ICFR in 2015 was due to accounting issues which were known to materially misstate the financial statements. Said differently, without recording the necessary adjustments, the financial statements taken as a whole would have been materially misstated. The remaining top five reasons for ineffective ICFR in 2015 were due to internal controls issues (which either did or “could have” contributed to material errors in the financial statements).

Moreover, the Audit Analytics report lists the following accounting-related ICFR issues as most commonly cited in adverse audit reports in 2015:

|

Ineffective ICFR issues related to accounting

|

Total number of attestations |

As % of total attestations citing ineffective ICFR

|

| Revenue recognition |

47 |

23%

|

| Income taxes |

36

|

18%

|

| A/R, notes receivable, investments, and cash |

34

|

17%

|

| Fixed assets and/or intangible assets |

29

|

14%

|

| Related parties and/or affiliates/subsidiaries |

27

|

13%

|

Effectiveness of ICFR not requiring auditor attestation

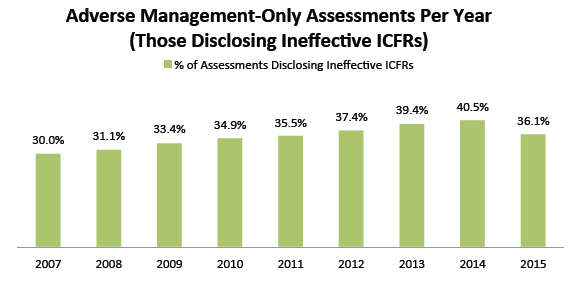

In contrast to the requirements in Section 404(b) for accelerated filers, non-accelerated filers and smaller reporting companies need not comply with this provision, thanks to the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, but they must comply with Section 404(a). Furthermore, non-accelerated filers were not required to implement Section 404 until late 2007.

For clarification, a non-accelerated filer, as defined by SEC Rule 12b-2, is public company whose public float (as opposed to market capitalization) does not exceed $75 million as of the last business day of the company’s most recently completed fiscal Q2. Furthermore, smaller reporting companies are those companies that meet the definition of a non-accelerated filer and had annual revenues of less than $50 million during the most recently completed fiscal year for which audited financial statements are available.

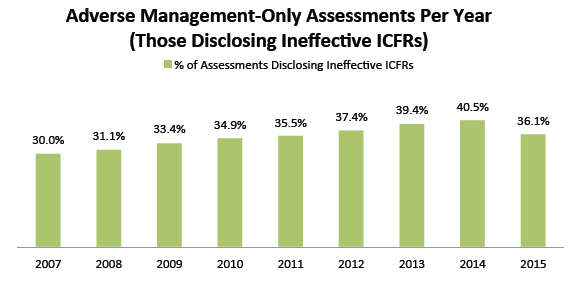

Having said that, the following chart shows the percentage of adverse management-only assessments relative to total management-only assessments on an annual basis in the last 12 years.

Interestingly, this chart shows a negative trend over the years, with a drop in 2015.

Key areas of adverse management-only assessments

The Audit Analytics report identifies the following internal controls issues with the highest frequency in 2015 in management-only assessments:

|

Ineffective ICFR issues

|

Total number of assessments |

As % of total assessments citing ineffective ICFR

|

| Inadequate accounting personnel resources, competency, and/or training |

985

|

79%

|

| Segregation of duties and/or design of controls |

893

|

72%

|

| Ineffective, non-existent, or understaffed audit committee |

388

|

31%

|

| Inadequate accounting disclosure controls |

246

|

20%

|

| Material and/or numerous auditor and/or management adjustments |

204

|

16%

|

To note is that two of the five top ICFR issues in the table above are also among the top five ICFR issues in adverse auditor attestations. A key reason for the provision in the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act eliminating the requirement for non-accelerated filers and smaller reporting companies to comply with SOX Section 404(b) was due to cost of compliance. Since we can see from the table above that overwhelmingly the two most common ICFR issues were inadequate accounting resources and segregation of duties/design of controls, it certainly seems reasonable to conclude that the cost of accounting resources is a relatively big factor for smaller public companies. While understanding that these statistics describe ICFR issues for public companies, to my surprise is that the third most common issue deals with inadequacies of the audit committee.

With respect to accounting-related ICFR issues noted in management-only assessments, the Audit Analytics report lists the following most commonly cited in 2015:

|

Ineffective ICFR issues related to accounting

|

Total number of assessments |

As % of total assessments citing ineffective ICFR

|

| A/R, notes receivable, investments, and cash |

95

|

8%

|

| Debt, quasi-debt, warrants and equity-related (beneficial conversion features) |

53

|

4%

|

| Income taxes |

48

|

4%

|

| Revenue recognition |

38

|

3%

|

| Related parties and/or affiliates/subsidiaries |

24

|

2%

|

The above table demonstrates that the most frequently cited accounting-related issues in ICFR was similar between accelerated and non-accelerated filers and smaller reporting companies. Furthermore, the Audit Analytics report indicates the top five accounting-related issues represented approximately two-thirds of the total accounting-related issues in 2015, both for adverse auditor reports and management-only assessments.

Summary

To put these findings into context for 2015, of those accelerated filers whose auditors issued an adverse SOX report, there was a pull toward ICFR failures due to accounting-related issues. On the other hand, companies that issued management-only assessments citing ICFR failures experienced significantly higher rates of ICFR failures due to internal controls issues as opposed to accounting-related issues.

In addition, the ICFR failure rates reported by companies with management-only assessments were significantly higher than the ICFR failure rates reported by accelerated filers. By applying a simple average over the last 12 years for accelerated filers and nine years for non-accelerated filers, the ICFR failure rates were 6.9% and 35.4%, respectively.

Finally, for additional context, I noted per review of the Audit Analytics report that in 2015 there were approximately 3,800 auditor attestations on SOX effectiveness filed with the SEC. With regard to management-only assessments, there were approximately 3,500 management reports filed in 2015 with the SEC. Therefore, the quantity of filings with the SEC between these two groups was comparable.

Source for charts: Audit Analytics August 2016 report, SOX 404 Disclosures, a Twelve Year Review.

Photo credit