As accounting practitioners, we live and breathe accounting standards. Without them we wouldn’t have a basis to record transactions or take supportable accounting positions. So, it goes without saying that reliance on accounting standards are necessary for fair, consistent presentation of financial statements. Those less familiar with accounting standards and the history behind them may make the mistake of assuming that any and all accounting standards are equally authoritative. This is simply not the case and for this reason I will focus today’s post on the hierarchy of U.S. GAAP and how it has changed over time.

History

To begin, a little history lesson may be helpful.

1975

Way back in 1975 the AICPA issued SAS No. 5, The Meaning of “Present Fairly in Conformity With Generally Accepted Accounting Principles” in the Independent Auditor’s Report (SAS 5). Beginning at ¶ 5, the Auditing Standards Board of the AICPA explained that there is no single source for U.S. GAAP standards, but that there are a number of resources, with Rule 203 of the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct requiring compliance with FASB standards, APB opinions, and AICPA accounting research bulletins. The degree of authoritative GAAP sources trickled down from there.

1992

Next, in 1992 the ACIPA issued SAS No. 69, The Meaning of Present Fairly in Conformity with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (SAS 69). This auditing standard clarified the GAAP hierarchy by introducing four levels, (a) through (d). As auditing practitioners implemented SAS 69, criticisms began to surface for a variety of reasons. First, this standard, similar to SAS 5, only really applied to auditors, not preparers of financial statements. Second, this standard was complex. And third, the GAAP hierarchy ranked the FASB’s Financial Accounting Concepts (CON), which are subject to the same level of due process as FASB SFASs, below industry practices that are widely recognized as generally accepted but that are not subject to the same due process (see ¶ 10 and 11).

2008

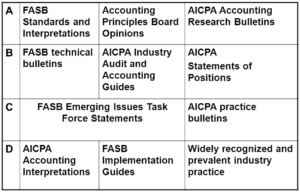

In response to these criticisms, in May 2008 the FASB issued SFAS No. 162, The Hierarchy of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (SFAS 162). The purpose of the standard was two-fold. First, it was designed to improve financial reporting by identifying a consistent hierarchy for selecting accounting principles to be used in preparing financial statements presented in conformity with U.S. GAAP (for non-governmental entities). Second, it was directed to entities (and not auditors) because it is the entity (not the auditor) that is responsible for selecting accounting principles for financial statements that are presented in conformity with GAAP. In a manner similar to SAS 69, SFAS 162 identified four levels in the hierarchy of U.S. GAAP standards, beginning with level (a) and ending with level (d), as depicted in the chart below. Once SFAS 162 was issued, the Auditing Standards Board of the AICPA withdrew SAS 69.

Just looking at the above chart can spin one’s head because let’s assume, for instance, that a widely recognized and prevalent industry practice is identified. This falls within level (d), the lowest level, in the above SFAS 162 GAAP hierarchy. However, in order to perform a thorough due diligence of the matter, one needs to either be familiar with or go searching for other applicable guidance that may be more authoritative, falling into levels (a), (b), or (c).

2009

Only a year later, the FASB rolled out the Accounting Standards Codification (ASC), with an effective date for interim and annual periods ending after September 15, 2009. Of interest is that the ASC makes it clear which accounting standards are “authoritative” and which are not. Simply put, if an accounting standard is included in the ASC, then it is “authoritative.” Conversely, if an accounting standard is not included in the ASC, then it is “non-authoritative.” An exception to this is that SEC-issued rules and regulations, applying only to SEC registrants, are authoritative even if they are not included in the ASC.

Understanding the way things were

As a forensic accountant, I deal with litigation involving accounting issues from the past. As I previously blogged about (see “Understand what standard or guidance was applicable at the time”), it’s imperative to put into context the accounting decisions that were made by knowing what accounting standard(s) applied a the time and, if multiple standards were in effect, which was/were most authoritative. I think it’s helpful to frame the issue by asking some relevant questions:

- What time period(s) is/are relevant to the accounting or disclosure issue?

- Depending on the answer to question 1, which of the above U.S. GAAP hierarchy standards was in effect at the time?

- If the issue relates to transactions post-ASC implementation, have there been any Accounting Standards Updates (ASUs) related to the standard? Although ASUs are not authoritative standards, it’s important to be aware of them.

Keep in mind that the FASB began issuing ASUs after the Codification went into effect. ASUs are numbered in the following format: Year first, then ASU number for that year (e.g., ASU 2009-14 was the 14th ASU to be issued in 2009).

By keeping the above understanding in mind practitioners can successfully apply the relevant GAAP standards to a historical transaction.