Today I’m writing about the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s (FASB) comment letter process. Prior to issuing authoritative accounting and disclosure standards, the FASB interacts with its constituents in a variety of ways to gather information that it may not have already considered. Having a strong understanding of this process can provide practitioners with meaningful context to assist companies in their application of the FASB’s standards.

To begin, the FASB is a private organization overseen by the SEC. The FASB sets standards, which become a part of U.S. GAAP accounting standards serving the broad public interest. To note is that since September 15, 2009 the U.S. GAAP accounting standards have been codified in what is known as the Accounting Standards Codification (ASC). In connection with setting these standards, the FASB has adopted an open decision-making process that provides for interaction between the FASB and its constituents. This interaction takes many forms, including comment letters. The FASB explains:

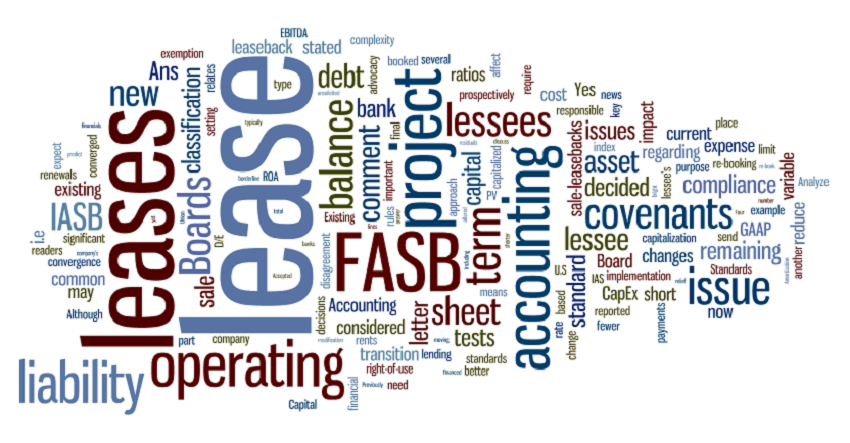

Comment letters are received from constituents in response to Discussion Papers, Exposure Drafts, and other discussion documents that are released to the public for comment. Comment letters, which become an important part of a project’s public record, are an important source of information regarding constituents’ views on and experiences related to issues raised in a discussion document.

Comment Letter Process

The following summarizes the FASB’s standard-setting process, which is governed by the FASB’s Rules of Procedures:

The part I want to focus on in the above graphic is step number five. When the FASB seeks to issue new authoritative accounting guidance, it commences by issuing exposure documents to solicit input. These exposure documents may include Exposure Drafts (ED), Discussion Papers, Preliminary Views, and Invitations to Comment. Often times the FASB issues an ED, but in some cases it may issue a Discussion Paper to obtain input in the early stages of a project.

The FASB typically issues EDs with a designated timeframe for respondents to reply, often in the form of comment letters, but also via public roundtable discussion and other due process activities. Depending on the nature and extent of the feedback it receives, the FASB may redeliberate the proposed provisions to accounting and disclosure standards. This, according to the FASB, is done at one or more public meetings.

Once all key concerns and issues have been considered and addressed, the FASB nears completion of its standard-setting process by issuing a final standard, in the form of an Accounting Standards Update (ASU). The ASU describes the amendments to the ASC.

Resources

When litigation cases or accounting consulting engagements involve the interpretation or application of accounting and disclosure standards, it is critical to understand the thought process surrounding the decisions that become part of a standard. Having a strong understanding of the FASB’s standard-setting process and knowing where to locate relevant information is key to building a strong position.

Practitioners have at their fingertips access to a host of FASB resources that can assist them in preparing arguments, opinions, or positions on a variety of accounting and disclosure topics. Some helpful resources include:

- Exposure documents previously issued by the FASB for comment, but are now closed for comment, unless otherwise stated. This link includes FASB documents issued after 2002.

- Responses received by the FASB in connection with its online comment letter process. One can read specific comment letters the FASB receives from constituents, including public accounting firms, SEC filers, and other organizations taking a keen interest in the FASB’s exposure documents.

- Unsolicited online comment letters from constituents. This link includes related documents dating from 2002.

- Exposure documents currently open for comment. I suggest these types of documents are less valuable to preparing arguments, opinions, or positions. However, understanding current deliberations may be applicable in certain engagements.

- ASU documents. Perusing certain aspects of these ASC amendments is a good way to obtain color and context to them. I have found the following ASU sections to be particularly helpful in obtaining the understanding I may be seeking:

- Why Is the FASB Issuing This Accounting Standards Update?

- Who Is Affected by the Amendments in This Update?

- How Do the Main Provisions Differ from Current U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and Why Are They an Improvement?

- Background Information and Basis for Conclusions

Application

I once worked on an engagement with a Fortune 1000 company that had become the center of a wave of negative media attention. In a move that was anticipated, the external auditor raised challenging questions about the company’s application of a particular ASU in light of the negative media attention the company had received. As an engagement team, in order to effectively address the external auditor’s concerns, we decided it was important to understand the details behind the ASU, including reviewing the comment letters the FASB received prior to issuing the ASU. This exercise shed meaningful light on the implementation issues that multiple constituents predicted would, and indeed had occurred with the company. Because of our ability to quickly look to relevant sources for reliable information, my firm was able to assist our client in navigating this challenge effectively and provide credible, supportable arguments to the company’s external auditor.